Two years ago I wrote about the evolution of the coffin in a blog entitled ‘From Coffins to Caskets: an American History’, so two years on it seems timely to explore its close relative, the shroud. After all, as the coffin became more elaborate, so too did the shroud. That’s to say that the stimulus for the shroud’s stylistic development was the coffin.

The blog is even more timely because the Coffin Works has been awarded an Arts Council Lottery Project Grant for a project centred around making examples of historic shrouds from the Newman Brothers’ collection. We don’t have any examples of shrouds in the collection pre-dating the 1940s or 1950s, so this will give us the chance to use our own trade catalogues to create earlier shrouds (see image below).

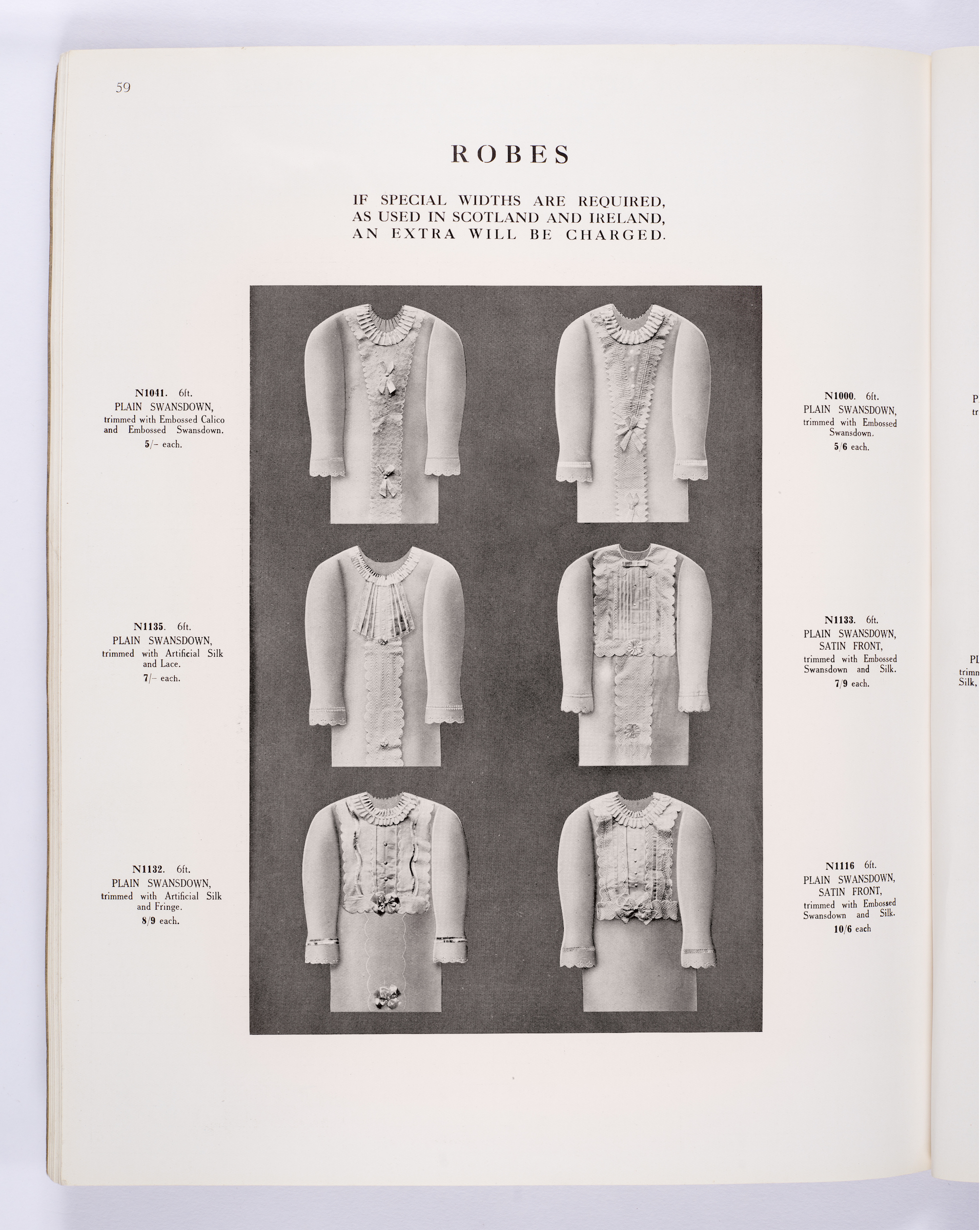

Newman Brothers’ trade catalogue dating from circa 1920s, illustrating examples of their shrouds. © Coffin Works’ Collection

The project is called ‘Dead Fashionable: Shrouds Past and Present’ and we’ll be working in partnership with practitioner, Laura Joyce, our former artist in residence. But, what’s most exciting about this grant is as well as allowing us to fill a gap in our collection, we can engage staff, volunteers and the public in the making aspect of this project, and future exhibition! We’ll also be exploring the topic of funeral poverty in three public engagement days.

The shroud and winding sheet

This blog explores the development of the shroud between the 16th century and first quarter of the 20th century. The terms ‘shroud’ and ‘winding sheet’ were used interchangeably in the 1500s and arguably up until the second half of the 19th century; the point at which the shroud developed its own distinct style.

As Julian Litten notes, the 16th-century shroud for the poor and lower middle classes was a large sheet that was gathered at the head and feet, and tied in knots at both ends, covering every part of the body. It resembled earlier Medieval practices and was a functional, yet modest way of preserving the deceased’s dignity. It was also economical, with very little cost involved, as the burial sheet was usually taken from the family home. At this point, linens dominated as the material of choice; after all, it was a biblical tradition as Jesus was wrapped in a linen cloth. Linen was also considered more fashionable than wool.

An artist’s impression of The Resurrection. ©Alamy Stock Photo

Litten notes that by the early 17thcentury, for the first time, faces, once shrouded, were now far from concealed. In fact, the norm was for men to be dressed in a cap, shirt and then wrapped in a winding sheet, or if female, a shift, ruffle-edged cap and winding sheet. In both cases, the face fully visible. The ‘shroud’, as more of a tailored garment, had not yet evolved as we know it today, but it was beginning to move further away from the simplicity of a burial sheet.

From linen to sheep’s wool

By the 1660s, a revolution in grave clothes was taking place. This was the catalyst for the early establishment of undertaking as a trade in its own right. But what changed in this decade?

An Act of Parliament in 1666 stipulated that all people now had to be buried in shifts, shrouds and winding sheets made from a woollen material, rather than linen. Clothes for the dead could only be made from sheep’s wool in fact.

This Act required:

“the dead, except plague victims and the destitute, to be buried in pure English woollen shrouds to the exclusion of any foreign textiles. It was so strictly enforced that it was a requirement that an affidavit be sworn in front of a Justice of the Peace or mayor (usually by a relative of the deceased), confirming burial in wool, with the punishment of a £5 fee for noncompliance.”

The ‘Great Plague’ of 1666 killed at least 70,000 people in London, and possibly as many as 100,000. Notice the shroud illustration in the middle of the page on the right-hand side, with knots tied at the foot and head. © Alamy Stock Photo.

Why was this enforced? For centuries the woollen trade had been important to the wealth and prosperity of England, but with the introduction of new materials such as linen, satin, and silk at competitive prices, some thought that the industry was under threat. Measures were needed to increase demand and what better way than encouraging people to use wool for the ever-present occurrence of death.

This Act did not really affect the upper classes who could afford to take the £5 fine, so many people chose to ignore it. Although this act was not formally repealed until 1863, it was largely ignored after 1814. By this point, linen, that once favourite, was superseded by ‘a new kid on the block’: cotton.

Woodcut of woman spinning wool in the 17th century. © The History Collection/ Alamy Stock Photo.

The winding sheet was ‘winding down’

Regardless of material used, by the end of the 17thcentury the traditional winding sheet was losing its popularity in favour of an open-backed long shirt with draw-strings at the wrists and neck, sometimes with an attached hood. It resembled a piece of clothing rather than a bed sheet and was the beginning of the shroud as we know it today. What triggered this shift? With the abandonment of the communal parish coffin, in favour of coffins for individual burials at the turn of the 17thcentury, it comes as no surprise that more attention was paid to burial garments of the deceased, and therefore the deceased themselves. The coffin was becoming a statement piece in its own right and more consideration was paid to its interior, and that included the person for whom the coffin was made. This after all was a business, and attention to detail and outward display was how a funeral furnisher and undertaker guaranteed future business.

Litten notes that the detail of the knot at the foot remained, but with the face no longer covered. This allowed family and friends to pay their respects while the deceased was laid to rest at home. This was a period of up to three days, and everything from the coffin, its fittings and linings, to the clothing of the deceased were being scrutinised.

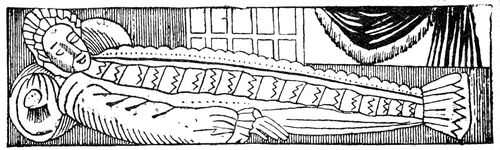

This illustration clearly demonstrates the cuffs and drawstrings at the wrist. © Shroud project gutenberg.

As the shroud began to become more ‘coutoured’, more attention was paid to position of limbs and the appearance of the deceased. To prevent flailing limbs, the ankles of the deceased were crossed over and tied together, while elbows and wrists were often tied and then ‘anchored’ to the body to keep shape.

John Donne (1572-1631), poet and Dean of St Paul’s Cathedral — monument in the Old St Paul’s, which he commissioned for himself before his death. He is shown wrapped in a winding sheet, standing on a funerary urn, his face, fully visible. © Chronicle/Alamy Stock Photo

1770 onwards

In between the transition of the winding sheet and the shroud were ‘coffin sheets’. In fact, coffin sheets were half way between both as they created the look of a blanket, and meant that the deceased could be dressed in a simple shift. As Julian Litten states:

“These sheets were tacked to the sides of the coffin and, after the remains had been placed into the coffin, wearing its shift, then the sheets were laid over the body, being turned back at the face if ‘viewing’ was required.”

The shroud had for the most part taken the place of the winding sheet from 1770 onwards. But far from making a dramatic exit, the winding sheet could still be found for sale in trade catalogues up until the second half of the 19th century. In fact, in many rural areas, the winding sheet proved to be more popular than the shroud even into the early 20th century.

It seems that at this point, shrouds (and winding sheets) came in up to twenty standard lengths, from twenty inches to six feet three.

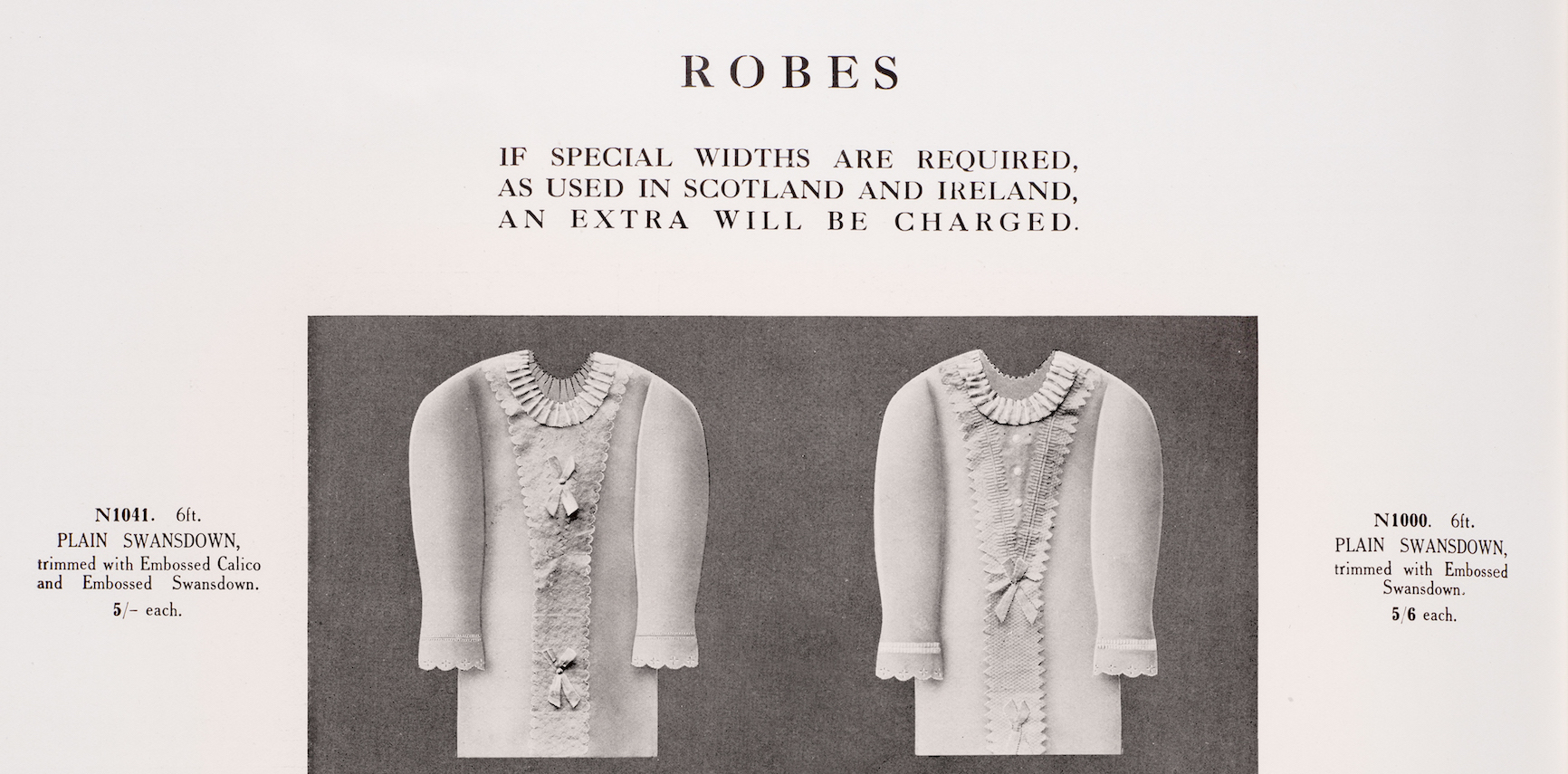

Newman Brothers’ trade catalogue dating from circa 1920, illustrating their full range of shrouds on offer. © Coffin Works’ Collection

The Shroud, as we know it today

The shroud really came into its own towards the end of the 19thcentury, with diverse styles developing for boys and girls, men and women. Litten notes that males tended to have sans bows, while women had a high-neck frill and less ‘panel ruching’ on the torso. In essence, women’s seemed to have been simpler. But, by the early 20thcentury, many companies were no longer distinguishing between men’s and women’s styles, but rather offering unisex shrouds.

By the close of the 19thcentury, materials such as swansdown and cashmere were replacing softer materials such as satin and silk, while flannel-type materials and stiffened cotton remained the most popular. Newman Brothers favoured use of swansdown, calico, silk and artificial silk in the 1920s.

Stylistic development of the shroud didn’t drastically alter after the First World War, which was the biggest turning point in the commemoration of death in this country. As a country we started to fear death rather than embrace it and our relationship with death in many ways mirrored the development of the shroud; it became stunted. The Victorians knew death and they knew it well. They accepted it as a part of everyday life. They knew what to expect of it, how to manage it. This attitude held strong into the beginnings of the 20thcentury, but the horrors of the First World War betrayed what the population thought they knew about death.

Victorian death-bed scenes, where loved ones could say goodbye were part of mourning the dead even after the end of the Victorian period, but the realities of the First World War did not afford this luxury. © Alamy Stock Photo.

The funeral procession was part of this commemoration and the ritual was played out according to accepted standards and rules, rules that governed ideals around what was considered a respectable or ‘good’ death. © LTD/Alamy Stock Photo

British soldiers bury a fellow comrade during the First World War. The ceremony of a funeral procession was also impractical in a war zone, forcing death to become a much simpler and practical affair. © Alamy Stock Photo

Their commemoration of death now proved incongruous with the realities of what it meant, no longer something natural, but unnatural and traumatic. When you take that into consideration, when appreciating that many victims of the First World War were in no fit state to be viewed, we can understand why less of a priority was given to the stylistic development of burial clothing that arguably would never be seen. The 1920s were therefore the apex of the shroud’s development, and mark a key chapter in our changing relationship with death in this country.

Special thanks to Julian Litten for sharing his time and knowledge in helping me write this article. Keep up to date with updates on our exciting project and look out for more blogs coming soon!

Sarah Hayes, Museum Manager.

For more information on shrouds, you can watch one of our short films produced in partnership with Julian Litten: