1894 was a good time to enter the coffin-furniture trade, but what you won’t often hear is that it was a dangerous time. And not because of industrial accidents or poor working conditions. This was a well-organised and tight-knit industry where outsiders were not highly thought of or easily admitted.

© Newman Brothers. Staff at Newman Brothers in 1912, maybe even including some of the workers who went out on strike in 1897.

In fact, by 1888 admission to this exclusive group was strictly regulated and you needed just two things in common: to be master coffin-furniture makers and second, to ‘doth your cap’, or sell your soul, as others saw it, to the reigning organisation known as the ‘Alliance’.

The Alliance was a group of manufacturers, led by Ingall, Parsons and Clive, with mutual interests, whose main aim was quite simple: to regulate trade and stop competition. Its underlying means of getting things done, was based on manipulation, corruption, threats and sometimes, it seems, even violence.

The Newman Brothers

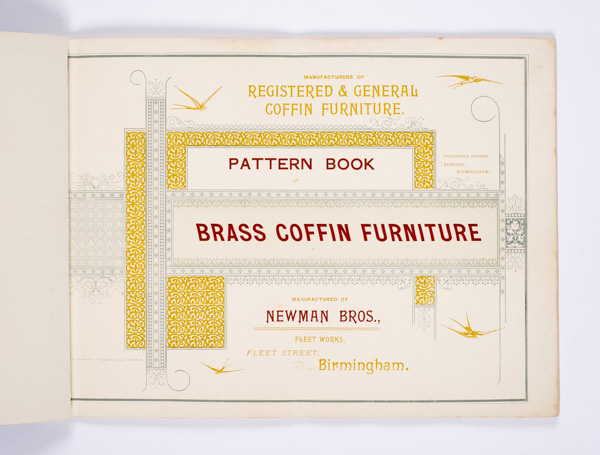

Why did Alf and Edwin Newman then, voluntarily choose to enter this unscrupulous world, actively making the move from brass founding to coffin furniture production? They must have been aware of this group and the influence they possessed. But, it would seem that rather than fully complying with the Alliance , they chose to sit on the sidelines and go head-to-head with this powerful combine. Why? Most likely to take a chance, fill a gap in the market, offer cheaper products, thereby challenging the ruling elite. And to do this, they had to play dirty.

Newman Brothers’ first trade catalogue as coffin furniture manufacturers.

Because of the ease with which coffin fittings could be made, pretty much any brass founder or stamping company could produce them, and there lay the problem. By 1888 there were around 19 master coffin furniture manufacturers in the UK, with the overall majority in Birmingham. But there was also a wider ‘black’ section of the trade, making cheaper products in the city. This was allegedly causing a fall in prices and profits, and the ‘masters’ did not like it.

‘Unhealthy’ competition

© Wikipedia. Harry Fowles, aka ‘Baby Face’ was part of the Peaky Blinders of the 1890s. Although they weren’t in anyway involved in the coffin furniture disputes, no doubt similar ‘groups’ operated to enforce the Alliance’s dealings.

18 of the 19 firms joined forces creating a monopoly or even a cartel, as some may argue. Together, they intended to eliminate any outside competition by encouraging others to buy from them, and them only. Rather than accepting a free market, the Alliance instead, made moves to control it, and this is where the recent production of Peaky Blinders comes to mind. But initial attempts weren’t as successful as they had hoped. It was clear that more severe actions were needed. They needed leverage – they needed control of a bigger force, what they needed was to control the workers.

Manufacturers did exactly that and joined forces with workers creating a new ‘union’ between masters and men. This was led by the Alliance and what they did was instrumental – they created a Trade Association, which outwardly appeared as though it was acting as a union for the labour force, but this was a front. And why a front? Exactly because workers didn’t decide when to strike – they were strategically encouraged to strike at manufactories which choose to operate outside of the Alliance’s remit. And their efforts were successful. They managed to engage nearly the entire labour force of the coffin furniture trade by offering 10% bonuses to any worker who joined them.

Bribery was the name of the game at the prospect of more money, workers forgot their sense of loyalty according to F. Owen and Co allowing:

“outside interference to cause them to forget the value of regular employment and good wages.”

The workers at this company were not so lucky and paid with their jobs after Owen replaced ‘disloyal’ workers with non-union men.

Unionising the workforce

Why was this so significant? Exactly because this Trade Association could now call workers to strike, thereby forcing certain manufacturers outside the Association to join it. The choice was join us, or we will destroy you from the inside, by taking your workers and stopping your production. Interfering with sources of raw materials and customers would seal the deal.

For the short term at least, this worked. And it wasn’t just the manufacturers who were ‘held to ransom.’ In April 1897, several union pickets were arrested for intimidation of a worker who refused to leave his job.

Don’t cross the picket line

Not long after, the Association tried their luck at Newman Brothers and the call to strike left Alfred Newman with no workers except for a few boys. Alfred was forced to concede and joined this new alliance between men and manufacturers. He did however fine six of his workers £3 each for breach of contact.

Things got even nastier and even more desperate. In order to prevent non-members from selling cheaper products, the Association promised undertakers and ironmongers a special rebate of up to 10% so long as they only bought from the ‘recognised’ firms in the Association. Newman Brothers would appear to be reconsidering their position within the Association, as they were threatened with price fixing and would be undercut by 25% if they chose to operate outside of the Association’s remits.

You mischief-making devil

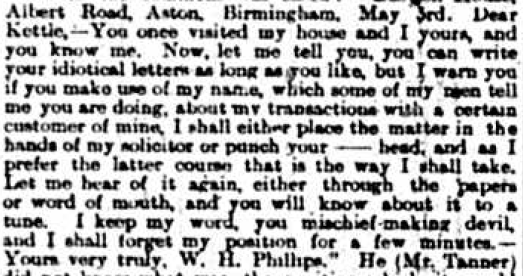

Edgar Kettle, Newman Brothers’ manager, went to the extreme of publishing letters in the newspapers warning customers against aligning themselves with an association that cared more about controlling their profits than looking out for their customers. He warned of the perils this would create for the entire industry and how this artificial control of the market stifled business and would let international trade in. This kind of bad press was clearly damaging for the Association and Kettle was warned off by a staunch member, Mr H Phillips. He not only appeared at Newman Brothers to personally ‘dissuade’ Kettle, but he was also fined £30, around £3,000 today, by Birmingham Police Court, for threatening Edgar in a rather explicit letter:

Seemingly, it was the physical threat to ‘punch your — head’ that caused Kettle to get a court summons for such threats. Edgar was accused of ‘playing dirty’ by trying to get ‘other’ men’s workers to strike. It would be easy to see Newman Brothers as a flagship in their attempts to promote a free market, when in actual fact, like others who resisted or rebuffed the Association, they were most likely just as concerned with their profits, and believed they would be hindered by the Association’s artificial control of the market.

Profits and principles seem to have been the driving force, and it was the precise action of companies like Newman Brothers, which in the end, made the Alliance and their Trade Association redundant. There were, by the close of the 19th century, just too many companies making coffin fittings to control. Newman Brothers survived this eventful chapter and emerged as one of Birmingham’s dominant forces of the 20th century.