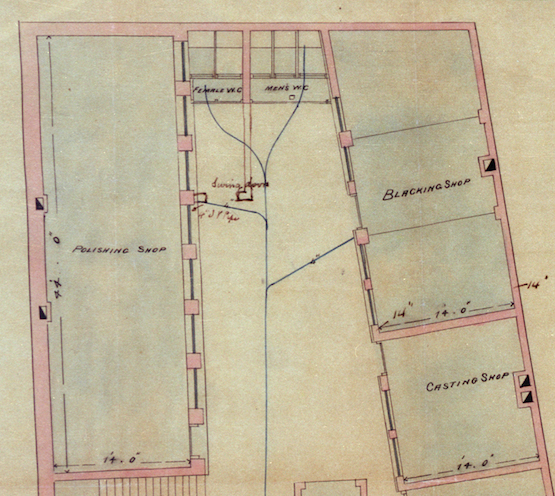

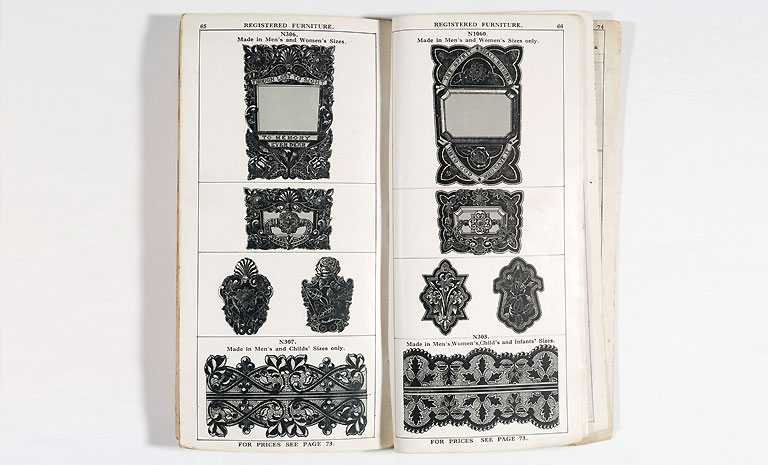

This breastplate design is classically Victorian.

How can we tell? First of all, it’s big. By big we mean it measures 300mm in width by 430mm in length. The average sized Victorian breastplate in the Newman Brothers collection is actually 320mm by 420mm. Size is very much one indicator of a Victorian piece and this is really as big as they got during this period. Through time though, breastplates get significantly smaller and are referred to as nameplates, with the average nameplate measuring just 180mm in width by 80mm in length today.

Design of a Victorian Breastplate

Design is also key, and this one object really sums up a Victorian’s attitude to death. First of all because it’s big. Second it’s bold and makes quite a statement, in this case, both in words and in design. The words quoted here ‘The Spirit shall return unto God who gave it’ are quoted from scripture, from Ecclesiasticus 12:7. This is a slightly ambiguous statement insofar as it reminds people of the fact that death is the ‘equaliser’ and you can’t take your riches with you. In contrast, the Victorians, who were preoccupied with social standing, saw death as an opportunity to define their social standing, and their wealth really was on show.

360 View of a Victorian Breastplate

Use the play button to rotate the object automatically, or alternatively you can drag the item with the mouse or your finger to move it around.

This item is in the following Themes:

Production

This breastplate is stamped. It was produced in Newman Brothers’ Stamp Shop using a machine called a ‘drop stamp’. Drop stamps are, in essence, heavy metal weights powered by a motor and operated on a pulley system. Stamped products were also cheaper than their ‘cast’ counterparts. This is because less work was involved in their production and cheaper metals were often used. Although some stamped products would have involved the use of brass, this breastplate is tinplate, which was one of the cheaper materials that Newman Brothers used. This was then finished in the ‘Blacking’ shop. Blacking involved a technique of painting the breastplate black with a heavy lacquer, a technique known as ‘black japanning’. It seems that black coffin fittings went out of fashion at Newman Brothers in the 1920s.

More on the Process

Japan Black is the name given to the lacquer used on iron and steel. At the time of its development the black colour which the lacquering process gave the finished product was something the West associated with Japan, hence the name. Japan Black used bitumen instead of the natural resins used in clear varnishing. The bitumen gave the finish its black colour.

When used as a verb japan means ‘to finish in japan black’. Thus japanning and japanned are terms describing the process and its products. However, Newman Brothers never described the process as japanning in their catalogues. Instead, they listed their black range of products under the following terms: ‘White and Black’, ‘Improved Black’, ‘Improved Black and Gold Enamelled’ and ‘Gold or any Fancy Colours’, ‘Gilt’ or ‘Gilt and Black’.

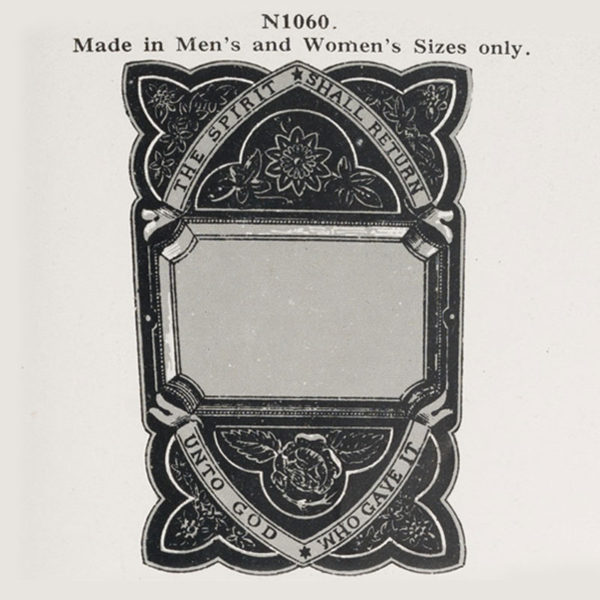

Below is an image from our original architect’s drawings showing the location of the Blacking Shop.