Origins of the Business

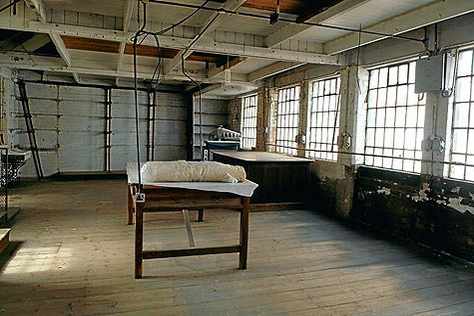

Newman Brothers was established in 1882 by Alfred and Edwin Newman. They were brass founders who originally specialised in cabinet fittings and worked from rented factories in other parts of Birmingham. In 1892 they commissioned architect Roger Harley to design them a manufactory in the Jewellery Quarter, dedicated solely to the production of coffin furniture – the handles, crucifixes and ornaments that adorned the outside of coffins. Two years later they moved into these new premises on Fleet Street, which they called the Fleet Works, but is today known as the Coffin Works.

In 1895, just one year after the factory had opened, the partnership between Alfred and Edwin Newman was dissolved and from then on Alfred ran the business as a sole trader.