The Shroud Room

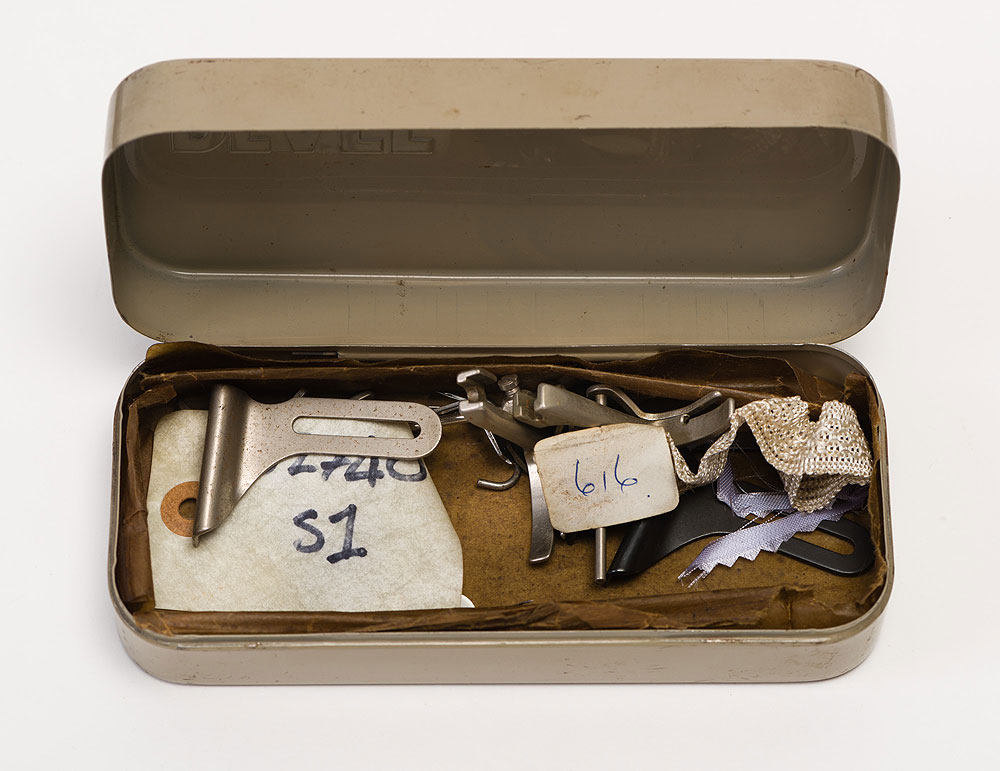

These sewing tins were found in the Shroud Room or the Sewing Room, as it was also more commonly known by the women who worked there. These women were referred to as seamstresses, and each of the sewing machine ‘stations’, where the women worked, had its own sewing tins, packed with cottons, needles and thimbles. The Shroud Room was the most important workshop on the second floor. This occupied the whole of the front range, and its height maximised the available light.

You can discover what was inside the tins below!